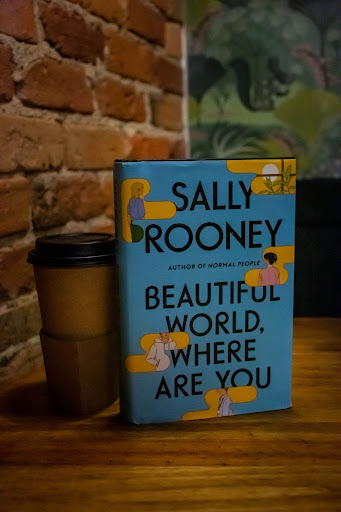

The day in question was, of course, none other than Sept. 7, 2021: the release date of Sally Rooney’s third novel, “Beautiful World, Where Are You.” (Although, if you are an indie musician or literary Twitter micro-celebrity, you have had it for months, along with a tote bag and, somehow, a promotional bucket hat).

“Beautiful World, Where Are You” is viscerally similar to Rooney’s previous work. The female protagonist is, once again, white, thin and intellectual, unhappy with her life circumstances and enveloped in a numb existence. She frequently touches the back of her hand to her forehead. She works at a literary magazine and spends her free time reading about and discussing European politics. She had no friends in high school and sat alone in the cafeteria. Like before, an emotionally repressed and unavailable man is desperately in love with her.

Much like her previous work, “Beautiful World” raises comparison, which Rooney herself hates, between Rooney’s life and the lives of her characters. Rooney has spoken in interviews about her fascination with care ethics, or what it would mean for the interpersonal relationship to become the basic unit of civic life as opposed to the individual, as it is now. Apparently, Alice, one of the novel’s main characters who is also a successful novelist in her 20s, frequently speaks about care ethics on book tours, too.

In the novel, Alice goes on a rant about how everyone assumes her fictional writing is autobiographical because of similarities between her characters’ circumstances and her own and how upset this makes her. Lamenting the fact that her personhood has to be publicly attached to her writing in an email, Alice writes, “It makes me miserable, keeps me away from the one thing in my life that has any meaning, contributes nothing to the public interest, satisfies only the basest and most prurient curiosities on the part of readers, and serves to arrange literary discourse entirely around the domineering figure of ‘the author,’ whose lifestyle and idiosyncrasies must be picked over in lurid detail for no reason.”

“Beautiful World” follows Eileen, the female protagonist described earlier, and Alice, Eileen’s college best friend turned bestselling author and vehicle for Rooney to insert opinions on being a young, accomplished author in this book. We are brought into their relationship through the emails they exchange as they navigate uncommunicative and dysfunctional relationships with men named Simon and Felix, respectively. Alice and Eileen became immediate best friends in college and are now on the precipice of their thirties. Alice has been released from a psychiatric hospital and just moved to a small Irish town to take a “break” from her career. Eileen is attempting to live in Dublin on an entry-level salary from a literary magazine, as she has for the past decade.

Rooney was a European debate champion in college, and “Beautiful World” is full of Rooney’s unmitigated — seemingly tangential to the narrative within the novel — sociopolitical musings more than any of her previous work.

Rooney discursively throws these opinions into the aforementioned, almost comically literary emails. One of my favorite emails swings from an art history analysis of a Manet exhibit into a recount of learning a family member has been hospitalized in the middle of a press tour, then into a comparison between a relationship with Jesus and relationships with other fictional characters, eventually becoming an explanation of feeling distanced from one’s parents by cultural sophistication. The whole novel is organized around these emails. “What if I sent you really long emails about capitalism every time I got laid,” reads a Tweet, perfectly labeled as a review of the novel, that sadly was probably deleted because I can no longer find it to link here/give credit.

What sets “Beautiful World” apart from Rooney’s first two books is a looming sense of existential dread. There is a muddy and ubiquitous feeling that the life choices one makes in college can turn out to be objectively wrong. I expected nothing less from Rooney’s writing as she, and her characters, age and leave behind the sense of possibility inherent in a novel set on a college campus.

The ostensible thesis of the novel is stated explicitly in a few of Alice and Eileen’s emails: “It seems vulgar, decadent, even epistemologically violent, to invest energy in the trivialities of sex and friendship when human civilization is facing collapse. But at the same time, that is what I do every day.”

At its core, “Beautiful World” is about the delusional beauty of messy and dysfunctional relationships set against the backdrop of today’s apocalyptic political landscape.

Any major fans of Rooney’s work will not be disappointed. “Beautiful World” is dense with Rooney’s characteristic sharp and witty dialogue, where every character’s rhetorical voice might sound the same if you give it a little too much attention. It’s dense with her ability to defamiliarize social structures, religion and, more concentrated in this novel, social media use.

It’s full of clinically written sex scenes, conversations about socialism and trips from one place in Europe to another. It chronicles relationships between unbearably booksmart people who simply cannot communicate their feelings with each other. It will leave your mind spinning, infected by its self-inflicted millennial despair.

Purchase it from Epilogue here.

Photos by Vivien Liebler

- A Great Day For Self-Inflicted Millennial Despair - October 1, 2021

- Growing Up With Clairo - July 23, 2021

- Never Meet Your Heroes - July 1, 2021