Who is American royalty?

Twitter erupted when Cosmopolitan published a 2015 cover dubbing the Kardashians “America’s First Family,” as many noted the Obamas were still fulfilling their stint in the White House at the time. Beyond this initial brouhaha, the magazine prompted various discussions about celebrity, influence and the oxymoronic concept of “American royalty” in a way that had yet to make its foray into our cultural lexicon.

Many still acknowledge the Kardashians as the closest thing to American royalty; they represent our obsession with fame, fashion and frivolity in a uniquely American paradigm. On the other hand, several point their fingers at political dynasties, notably the Clintons, the Bushes and the Roosevelts. Others suggest the avaricious robber barons of the Gilded Age, posing in front of Biltmore, a veritable castle, on Asheville trips as a tangible legacy of the ancient history of the Vanderbilts and their wealth. Some would look at others crazily if they didn’t immediately say the Carters.

This is what obscures the objectivity of the oxymoron; without a designation, we lack metrics for what constitutes American royalty. Is it fame? Wealth? Political influence? There is no consensus.

When you overlook the carnage of white imperialism, expansion and genocide, it is, in a very clinical sense, miraculous how 13 fledgling colonies overtook the British Empire– throwing their hands at an unfathomable gamble by pursuing democracy. We don’t have a royal family, and first families are ephemeral at that. The sanctity of that idea—that anyone can make whatever progress they want and that we lack hereditary titles—is what makes our system so hallowed. Furthermore, it is also what makes the idea of American royalty so controversial.

Despite these nuances, there is one family that jells affluence, celebrity, politics, fashion and culture in a history that authors the most promising argument for the closest thing to American royalty: The Kennedys.

Our seemingly endless fascination and our obsession for this family and the glamor they brought to a national level is poignant and tragic—living on from the memories of our grandparents to Pablo Larraín’s Jackie. That eponymous first lady—who summered in Newport, honed her Francophilia at a Seven Sisters and most importantly elevated a new generation of arts and culture to the national stage. She breathed fresh air into a presidency that was suffocating from the comparatively insipid Eisenhowers.

The Kennedys were young, fresh, attractive, stylish and Catholic—which meant something in the zeitgeist of the time. In juxtaposition to the previous administration, this meant something in the Civil Rights Era. The legend of Camelot and what it meant for this country is too ineffable to give justice to in one article, but it would be negligent to leave out.

Camelot meant an affinity for arts and culture; it meant celebration of American theater and joy in a time when nuclear winter was all too real. It meant pride. It meant an end with blood-stained pink Chanel suits, and it couldn’t have been Camelot if it hadn’t been so transient.

“There will never be another Camelot.”

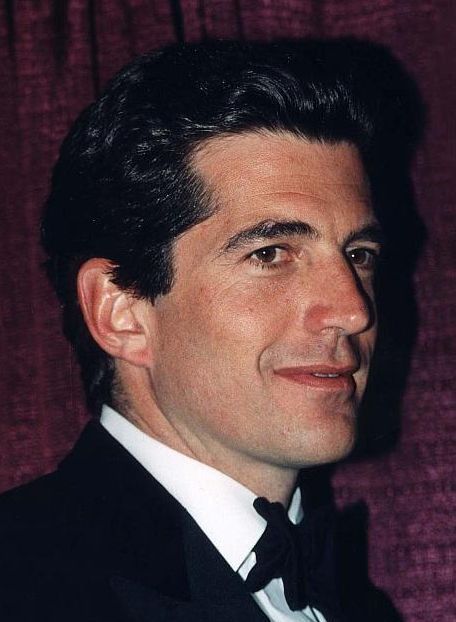

If Kennedy was our king, JFK Jr. was our crown prince. Our grandparents fell in love with John John standing in salute at the casket of his late father’s funeral. It was all too tragic and surreal, and, while this three-year-old concluded Camelot and its inimitable majesty, he also made his foray into our national conversation, a legacy that would evolve far beyond that agonizing reel.

JFK Jr. became the Sexiest Man Alive. Media flocked to his frisbee games in Central Park, sweat beading off his mobile body as if he was part of some Bruce Weber photoshoot. He was a terrible athlete. He was put on probation in undergrad and failed the bar twice. He matriculated at Brown before graduating from a T14 law school. Despite these contradictions, JFK Jr. had a prescient quality that abstracted him from the high expectations of his very famous last name: he had vision.

Perhaps the incubator for this vision was his mother’s ability to shield her children from the complications of their father’s assassination, removing her family from the rest of the Kennedys in Massachusetts. He was geographically and familially removed, tacitly distanced from the family legacy due to the fractured nature of his upbringing. One thing he wouldn’t be able to escape was his family curse.

His academic fallouts were the opposite of his sister Caroline, who graduated from Columbia Law in the top decile of her class. John had always wanted to be an actor, but his mother wouldn’t let him pursue it vocationally, and in a way, his creation of George seemed like a compromise between his and her aspirations.

George’s inaugural 1995 magazine featured a powdered Cindy Crawford in an iridescent crop top and frock coat: she was George Washington incarnate. It was quite controversial. It was young and fresh and attractive and stylish. Posing a supermodel as our nation’s earliest, most important figure in American mythology in a gender bending transformation was truly ahead of its time; today, such a cover would be celebrated, not goaded.

Kennedy’s brainchild was really the first prominent nexus of fashion and culture in a casual manner aimed at the general public. Decades before Vogue profiled Kamala Harris as its cover star or before Politico analyzed the labor model of the fashion industry in its podcasts. The then-wildly bizarre concept that regular people would even want to consider politics through such a nonchalant, culturally-fused lens seems so obvious and normal now that the gravity of its approach appears trivial.

John saw this. He saw that “not just politics as usual” had a place on everyone’s mind. It is so natural and integral for politics and culture to be intertwined because, in abstract, they are more synonymous with one another than we allow ourselves to admit. That connection would not be made in similar capacities until decades after when “fashion” magazines started chronicling political issues, and when “political” magazines started chronicling “fashion” issues.

If John had vision, it was too far in the future. George circulated for a little over five years, struggling after John and Carolyn’s deaths in 1999. His lurid attempts to save the magazine—throwing trinkets here and there to stir up frenzy, like posing nude in a 1997 issue and editorializing his own cousins at one point—were to little avail.

“Politics overlapped with Pop Culture in such a limited number of ways,” wrote Spy magazine of the publication’s final issue, rationalizing its precipitous decline. That contention sounds laughable in today’s world.

The fact that John had such vision was overshadowed by extrapolated political ambitions, his last name, the diatribes on his wife, his attractiveness and his failures as an attorney. Perhaps he saw too far ahead in to a world that came crashing down before his eyes.

Even greater irony manifests when positing him and Carolyn at the juncture of so many aspects of George: politics, fashion, youth, zeal. They were living representations of how Calvin Klein’s it girl could marry Camelot’s crown prince and make a life together in Tribeca, a home so much more vibrant and dynamic than the stagnation of the more familiar Upper East Side. There, they could retreat from paparazzi in beanies and Stan Smiths– living as something glamorous ,beautiful and sacred; they were swans. But nothing good lasts forever.

His marriage and his magazine would survive the same number of short, fleeting months.

John and Carolyn’s Atlantic ends seemed to be the last portent of a changing zeitgeist. The world had already lost Diana and Gianni, and we had no way of preparing for the way 9/11 would rattle our bones and run our blood ice cold. New York changed, and a city of opportunity became a city of dread, a microcosm of the coming decade into which we were born.

Who knows what John and Carolyn would think of today’s youth, who have finally, at last, jelled the politics-is-culture-and-culture-is-politics reality he pioneered almost three decades ago. We can only appreciate his vision for a generation that could view politics as something as tangible to our identities as culture, for in the end they are much more synonymous than our predecessors have allowed us to believe.